- Australian wildfires in 2019 and 2020 made thunderstorms that funneled smoke into the stratosphere.

- Two new studies suggest that the smoke depleted ozone, which protects Earth from harmful radiation.

- The ozone hole's recovery is lauded as a climate success story, but wildfire smoke could slow it down.

Wildfire smoke may slow progress on one of the most widely hailed climate success stories: healing the ozone layer.

In the 1980s, researchers discovered that a class of household chemicals called chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were eating a hole in the ozone layer, which protects Earth from cancer-causing radiation. A 10% decrease in ozone levels would result in an additional 300,000 skin-cancer cases worldwide, according to a World Health Organization estimate.

World governments banded together to phase CFCs out of household products, like refrigerators and hairspray, when they signed the Montreal Protocol in 1987. CFC emissions fell, and the ozone hole over the Antarctic began to close. Now the ozone layer is on track to fully recover by 2060, according to a scientific assessment from the United Nations and the World Meteorological Association.

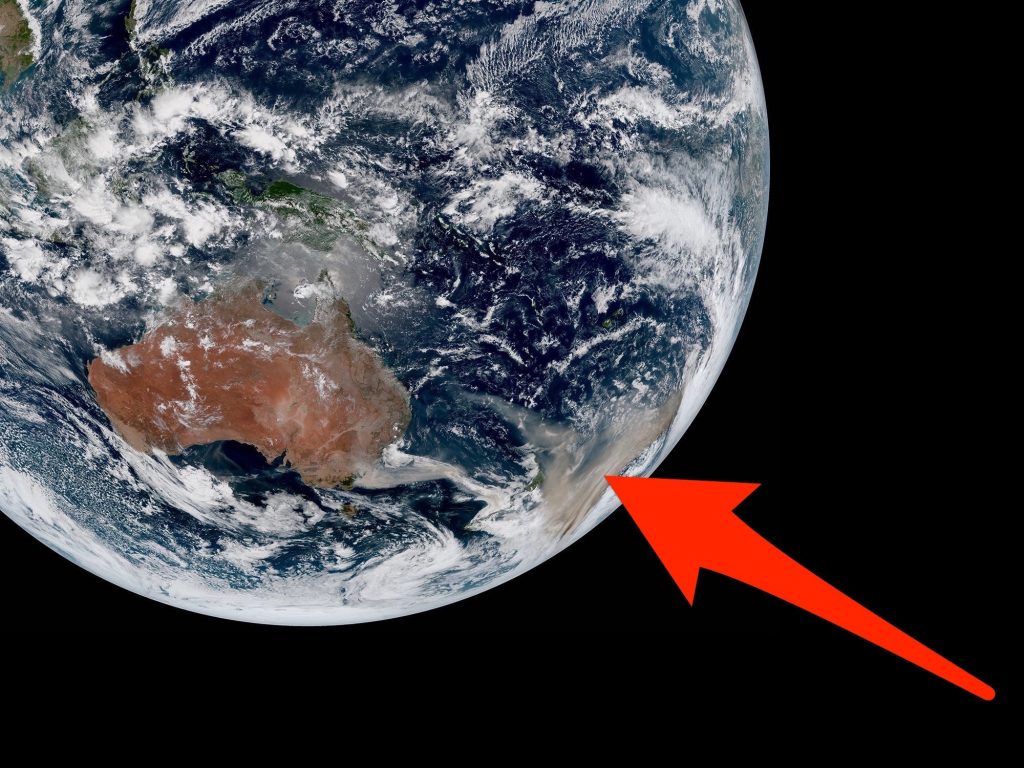

But an unexpected new threat — wildfire smoke — might slow that recovery, a pair of recent studies suggest. Researchers discovered that Australia's "Black Summer" wildfires in late 2019 and early 2020 created a cloud of smoke so large that it rose into the stratosphere, circled the southern hemisphere, and triggered a chain of chemical reactions that destroyed ozone.

"Smoke was not supposed to do this," Peter Bernath, an atmospheric chemist at the University of Waterloo, who co-authored one of the studies and led the other, told Insider. "It was completely unexpected that smoke made these atmospheric changes. So this is new chemistry."

The smoke was associated with a 1% decrease in ozone at southern midlatitudes in March 2020, according to calculations in one of the studies, published this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. One percent may sound small, but it's significant, considering the ozone layer is rebuilding itself by about 1-3% every decade.

The second study found that the smoke led to a rise in compounds, like hypochlorous acid, which react with ozone molecules to break them apart. Researchers aren't sure how the smoke causes an increase in these reactive compounds, but they are confident that this is what caused the ozone levels to dip in March 2020. That paper was published in the journal Science on Thursday.

Within about nine months, the smoke had cleared from the stratosphere, and ozone had recovered to pre-wildfire levels. But the researchers suspect that other major wildfire events, like the 2017 and 2020 blazes across the Pacific Northwest, could have a similar ozone-depleting effect.

Smoke probably won't undo the ozone layer's healing, Bernath said, but it could slow it down. In recent global climate and wildfire reports, the United Nations warned that fires will become more frequent and more severe as global temperatures rise. That could mean more enormous smoke clouds that reach into the stratosphere and destroy ozone.

"As severe wildfires increase in number, they will play an increasingly important role in the global ozone budget," Bernath's study concludes.

Australia had the first 'super outbreak' of fire-driven thunderstorms

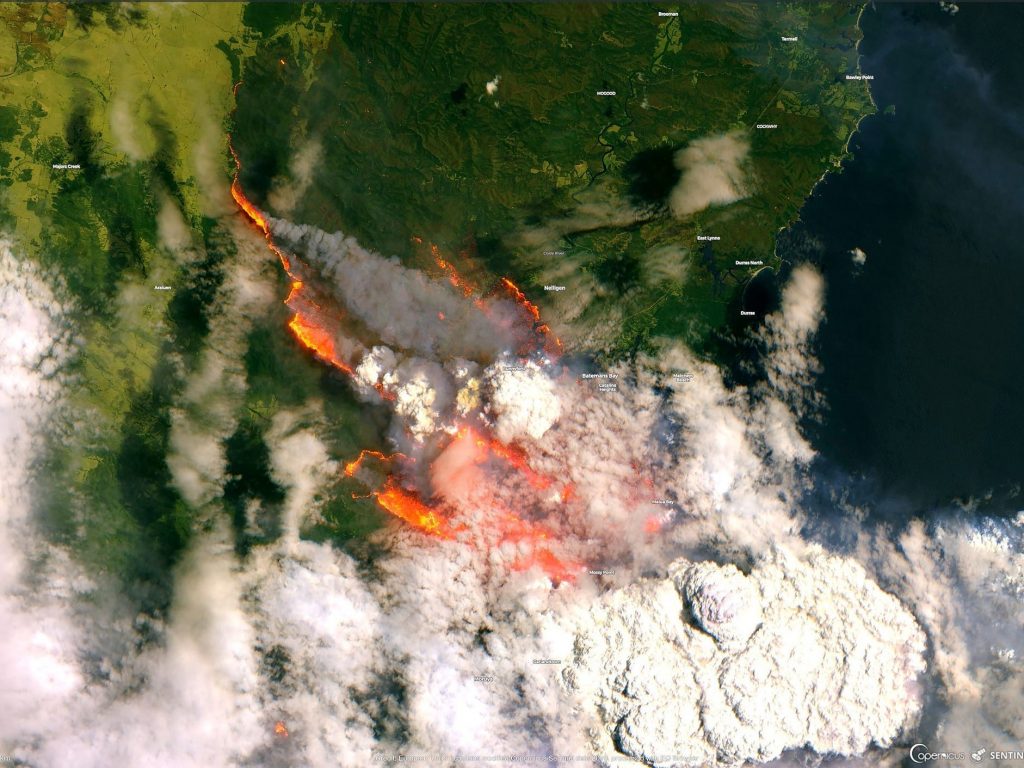

When wildfires burn hot enough, under the right conditions, their smoke creates its own weather. It billows up into anvil-shaped thunderstorms called pyrocumulonimbus clouds, or "pyroCbs" for short.

Smoke cools and expands as it quickly rises miles high, allowing water vapor to condense on the ash particles and create a cloud sitting atop the smoke column. The fires below fuel hot updrafts that sustain the thunderstorm and funnel smoke into the upper atmosphere, like a chimney.

That's what happened above Australia in the final months of 2019 and beginning of 2020. As fires consumed about 50 million acres of land, they created about 38 pyrocumulonimbus clouds, which persisted for days.

More than half of those clouds reached the stratosphere, according to research led by David Peterson, a meteorologist who studies pyrocumulonimbus clouds at the Naval Research Laboratory.

"That's why we refer to it as the first pyroCb super outbreak," Peterson, who is not affiliated with the new studies on ozone, told Insider.

It's unclear how often fires will shoot ozone-destroying smoke into the stratosphere

Pyrocumulonimbus clouds that reach into the stratosphere could become more common as the climate warms, but for now, that's hard to forecast.

"It's not just the fire. You need a certain atmospheric condition that allows for the thunderstorm to develop," Peterson said, adding, "Just because you have more wildfires doesn't necessarily mean you'll get more pyroCbs. It's really, how often do you have this synergy of the weather and the fire at the same time?"

That's an area of ongoing research — a "frontier topic," in Peterson's words. Nobody knows the future of wildfire-smoke storms and their ozone-destroying potential.

Bernath and his colleagues aren't even sure how wildfire smoke leads to compounds that react with ozone. They think that the hydrated, acidic surface of the smoke particles triggers chemical reactions that wouldn't otherwise take place in the stratosphere, creating new compounds.

"The smoke particles have a reactive surface, and that surface catalyzes this chemistry that destroys the ozone," Bernath said, adding, "So we kind of know what the smoke is doing. And we have some clue what the surface of the smoke particles looks like. But we don't actually know what particular reactions are taking place on the surface."

Laboratory research that inserts smoke particles into a stratosphere-like environment, and documents ensuing chemical reactions, could fill in the blanks.

Bernath and his colleagues are also studying satellite data from the fires that engulfed the West Coast of the US and Canada in 2020. Those blazes created pyrocumulonimbus clouds, and Bernath suspects that smoke had its own effect on ozone levels.

"This field of research into pyroCbs and their effects is relatively new, especially compared to other types of wildfire impacts," Peterson said, adding, "We learn a lot, but then we get a lot of new questions."

Dit artikel is oorspronkelijk verschenen op z24.nl